It thinks that I can’t see it, but I can.

I walk up the stairs to my room. Something repellent moves from the corner of my eye, but I ignore it. Now is not the time. It will be gone by the time I look. My back feels exposed and raw. No. Not yet.

I almost expect it to be in the hallway mirror. It likes to do that: staying there in the glass glowing and rotting long enough for your heart to lurch and a keening sense of wrongness–of wrong clarity–yanking your insides down, down, down like a bad realization.

I turn the corner–it always loves to hide in corners–near the bathroom and I half-expect to see its sickening, unnatural face there. But not yet. The floor creaking breaks the stillness of white noise in my ears and then, I know.

I get to my room and then turn on the light. I see it for a few seconds!

Despite myself, my back is ice. I take the time to breathe. The last time it did that, it was a pale woman in a tattered dress and a shredded eyeless face in the middle of the night. I blinked once and she was right in front of me. Then she was gone.

I climb into my bed despite the other memories. It’s worse when you can’t see it. I lean my neck against the headboard as I put my laptop with its makeshift worn plastic box prop onto my stomach. The unsettling feeling that’s been with me for a while now is prickling stronger. It likes it when I think about it. It likes it when you think about all the other times it got you before: playing its sick game of tag, and hide and go seek.

And it cheats every time.

See, it knows. It knows that I know it’s there now. It can smell it on you: that mix of anxiety and anticipation that is human fear. I move my fingers across the small cramped keyboard: looking at my email while I know it’s watching me.

Click.

Click.

Click.

My bladder is filling up. It’s getting closer. I can feel it grinning now. I’m trying not to think about the times I don’t see it … the times I don’t see it as it rocks my bed in the night, or touches me in the dark … even under the covers …

It is the only thing that can be both hider and seeker in its games, but whatever else it is always a predator.

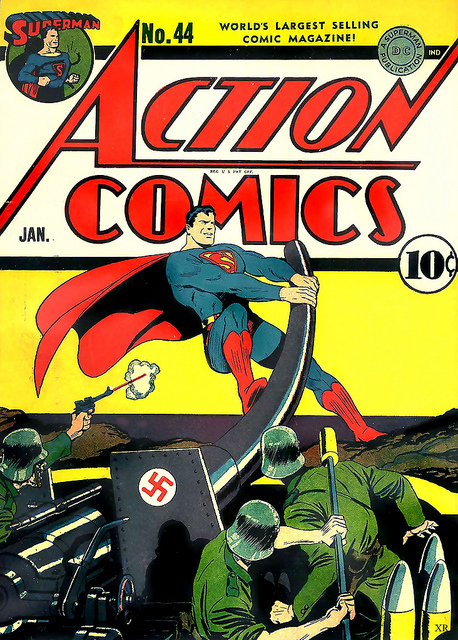

I surf the Net to a page displaying an animated GIF of a Boo Diddley from the Super Mario games. I watch the small pixelated white cartoon ghost making faces at the back of a pot-bellied plumber, soaring towards him with a red-eyed gaze and a vicious fanged grin before the latter turns around and it covers its face: as though fading out of reality with transparent chagrin.

This ridiculous image reinforces my knowledge. I slowly look over the top of my laptop. It’s standing at my desk chair: a hideous, twisted thing out of nowhere, the farthest thing from a cute cartoon or anything else from this world …

And I will it into place.

It’s all over: just like that. I get up and keep my eyes on it. It seems like it’s struggling, but it can’t move. It is fucking repulsive. Every part of me wants to be gone from it. My skin and the nerves underneath want to crawl away from the thing, as my bones become stone. But I make myself look at it.

“I have to admit,” I tell it, as it crouches there misshapen on the carpeted floor, “I made all of you well, but I think I made you best of all.”

I feel the power of my will wash away the dregs of my fear as animal repulsion turns into a strange kind of fascination. Its body is crooked and stunted. The thing is naked too: its skin glistening with a wet kind of pale blue luminosity. It doesn’t have any eyes or ears and there is a flat line, almost like a fine horizontal gash, where its mouth could have been.

I walk slowly towards it, “Just forms in the dark,” I move slightly off to the side, “You were always there. I wanted to see … I wanted to see if I could make something like you: if you’d attack your creator.”

It makes no sound at all. The grim fascination is quickly becoming a morbid disgust: like seeing a particularly bizarre form of insect intruding into a human living space. It shouldn’t belong here, but somehow it does. And that bothers me. I pick up the baseball bat I left leaning on the side of my dresser.

“You thrive on uncertainty and seeming on the fringes of things,” I lift the bat over my head in a two-handed grip, “Sure, when you startle someone, you are all tough shit. But here, in the light, without your cover you look unreal. Fake. Just as I made you.”

It’s that age-old admonition to never reveal the monster in a horror story. Otherwise, it has no more power. It never did. I begin to swing the bat downward … until it chuckles. It is a faint, rustling form of wheezing. My bat is inches away from its face. The thin line that is its mouth twists and I more feel it than hear it speak.

“You didn’t make us.”

I … can’t move. It gets up. The fact that it is several inches shorter than me doesn’t make me feel any better. I can feel it managing to look at me without eyes. It speaks again.

“We were forms in the dark. Things in the shadows. And we’ve watched you,” its voice scraps like leaves across the pavement, “We watch you as you are born in your own filth and blood. We see you become gangly, awkward beasts with sweet-smelling hormones: though you aren’t yet ripe. You put your dripping parts into each other to make more squalling things in perpetual pain and fear of the dark and you delude yourselves into thinking that you are not alone.

“And that is the sweetest of all.”

I’m willing my eyes on the thing I made, willing my arms to swing down, to back away …

“The broken bones are an added bonus, but they aren’t necessary,” it explains to me, “the shattered dreams add spicing. Sometimes, you slit yourselves open, or smash yourselves into adolescent pulp before your maturation, before your time … as if you already know.”

It’s the first time it’s ever spoken to me. I want it to shut up. I want to make it die.

“No. Our favourites are the ones that age to ripeness and perfection: the ones that gradually begin to see themselves for what they really are, what we see you to be,” the thing’s thin mouth peels back, revealing long and yellow stinking teeth, “Hollow brittle shells of dark churning space against the pressures of gravity. You are born in pain, and you live in it, and–in the end–you die in it. Despair aged to perfection has a unique flavour.

“And then you hope it ends in death.”

The last thing I want to hear is the sound of its laughter. It reaches a long, slick bony talon towards my face, “You see, it’s not so much that you created us … it’s that we created you. We made you: to suffer in all the little banal ways first. All the hidden, shameful, unspoken, lonely human ways. We get to watch as you die slowly inside and out … and when we watch, we feast. We feast as you return to the filth you came from. We devour you as you return to the dark … from where we crafted you.

“And we love your sense of self-delusion. Because false hope … it is our delicacy.”

My bat slams down into its skull. It smashes into its face. It’s more like my body is the one in fury, my adrenaline speaking with my voice, my voice being my hands, my feet, and my weapon while my blood is my sheer unadulterated hate. My arms and fists are aching. Somehow the bat is gone and I’m beating the thing. I’m beating it to a pulp. I can’t think. I won’t think.

My fingernails gouge into its slimy skin. My teeth sink into ichor. I taste bitterness. A part of my mind knows that it will be over soon: that others will find me. Maybe it will be my family, or more of these … things. They will find me in my torn clothes with another’s blood on my chin and torn flesh in my mouth with the pulped remains of another sentient being under me. Or maybe they will find me alone, with no one else, crazy and without my mind. Perhaps they’ll take me away where the things will keep laughing at me in the dark: amused enough by my new … enlightenment to let me live on like this.

Perhaps it was never a game of tag or hide and seek. Maybe it was just a joke with the following punch-line.

I am a monster. And I don’t care.

Maybe that’s what I’ve always been. Maybe I’ve finally found what I’m really looking for. Somehow, I see myself smiling just like the Boo still flashing on my laptop screen: looking away from myself and grinning … wickedly.