I’ve been rereading Pop Sandbox’s Kenk: A Graphic Portrait and I kind of wish that this comics work had been published when I worked on a previous assignment of mine.

In one of my previous Graduate courses, our class had to read Carl Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth Century Miller. It basically dealt with the idea that an individual can not only embody the culture that they come from, but that that person can represent different kinds of culture and actually interpret cultural information differently for themselves. Really, what I got out of it was that an individual can create their own world or mythic reality from information they have access to from their own culture.

As for why the work is called The Cheese and the Worms, it’s due to the fact that it focuses on the record of a man named Menocchio who compared the world’s creation to be not unlike that of rotten cheese. I’m not making this up: the Roman Inquisition that interrogated and took testimony from him apparently got this account from the man. So obviously, I felt compelled to do a presentation on this and focus my course paper on it because, well, look at the title and the subject matter. Really: how could I not?

I think that I found the most interesting about Menocchio himself was the examination of how he possibly came to the conclusions about the world that he did. He was not born of nobility or the upper-class in Italy, but rather came from a merchant culture. As such, while he was literate and he had the means to buy books, he also grew up with an oral literary tradition: a culture that passes on lore through the ages and word of mouth.

Ginzburg seemed to really like to point out the strangeness of this figure of Menocchio: how he was almost an intermediary between the oral and the written as well as peasant and “higher culture.” Menocchio himself lived during a time of transition between oral culture and the development of the printing press and written literacy: a revolution of sorts. Menocchio existed during the time of Martin Luther’s Reformation: where the ideas of Catholicism and Christianity itself were being challenged by the new Protestant movement using said printing presses. It is also worth mentioning that Ginzburg liked to examine colportage–cheaply printed chapbooks detailing songs, tales, and the lives of saints–as a backdrop of Menocchio’s literacy as well.

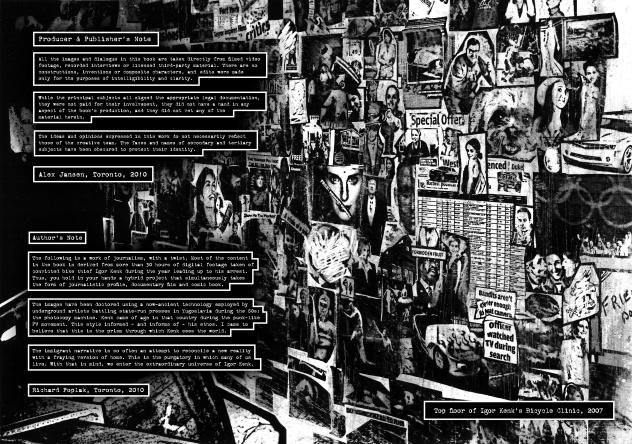

All of these traits and more are eerie parallels with Richard Poplak’s observations about Igor Kenk. Kenk grew up during a time between socialism and capitalism in Slovenia of the former Yugoslavia. One thing that Richard Poplak likes to point out is that it was also during this time period that common citizens in Slovenia were allowed access to photocopy machines: mechanisms of distributing information that were originally in the charge of the State. The counter-cultural Theatre FV 112/15 group– also known as the FV movement–used photocopiers to create a collage art known as FV Disco: a form of which–thanks to the artist Nick Marinkovich–Kenk also utilizes. This was the time and conceptual place where Kenk developed as an adult.

As such, Kenk also possesses a very unique world-view based on the transitional culture of his time: the idea that all things can be recycled and that you need to choose to struggle in life in order to survive as a person: which is part of what he seems to call “The Monkey Factor” or survival. From what I understood of this book, his notion of “recycling” also seems to mean reselling stolen bikes as well as hoarding. As an aside, the fact that Kenk believed the system of debt, borrowing, and capitalism to be doomed is also linked to his philosophies and it’s only now, years after I read the first time, that I wonder what he would think of the Occupy movements back in 2008 before his arrest, and what they might think of him now.

Igor Kenk came from a social order that was radically changing and between extremes. He was considered to be a Math prodigy and did well in his education. For a time he was even a police officer in Slovenia–surviving their harsh regimen–until he was discharged, and then proceeded to cross the border into other countries to get goods as Slovenia’s political alignment and its economy changed. Then he eventually came to Canada and became something of a merchant himself by selling and fixing bicycles in Toronto.

What I’m trying to say is that both Kenk and Menocchio are products of their time and culture, but at the same time how they chose to interpret their changing cultures was very idiosyncratic to them. In other words, they created some very unique world-views. And both of them arguably paid for it by the powers that be: Menocchio with his life for not recanting his beliefs to the Roman Inquisition and Kenk doing jail time and losing his Bicycle Clinic for the thefts he was charged with.

All of the above can arguably be considered gross simplifications, of course. In my paper that dealt with the implications of Menocchio, I pretty much say the same thing more or less. But I think the reason I’m attempting to compare two men from entirely different time periods, cultures, and countries is due to a greater issue: namely, why are they important?

I mean, come on: neither Menocchio nor Kenk would traditionally be considered important in a historical sense. In the grand scheme of things, someone might say that, while these parallels are interesting, who the hell cares?

The reason that I care, and one of the reasons why modern historians, journalists, and–in some ways more importantly readers–find these accounts so important is because they are narratives that deal with real people. It’s true that neither Menocchio nor Kenk are politicians, or artists, or even popular cultural figures in themselves but they are people that–while arguably normal or common in terms of class or historical significance–symbolize greater historical and cultural shifts by just being who they are.

They are ordinary people with very un-ordinary perspectives and there was a time where we would never have even known about them: or at the very least we’d only get a summary of them in passing … or at least we’d get something like this from a dominant or “higher cultural” narrative. Because there is one thing I keep coming back to in my head: it is the idea of oral history.

What is oral history? We know that oral culture or literacy is something that is passed on verbally from one storyteller to the next throughout many generations. But history, as Westerners, understand it is derived from the ancient Greek word historia: which is something along the lines of scientific inquiry or observation. Oral history, from my understanding, is thus something of verbal origin that is written down for other people to see.

Menocchio’s “worm and cheese world” survived through the written accounts of his interrogators, whereas Kenk seems to have actually been interviewed by the book’s producer Alex Jansen and filmed by Jason Gilmore as he espouses his world-view of “Monkey Factors and recycling” in that context.

Oral culture in our world is very different in that we have sophisticated image and audio technology to preserve and record the spoken word, and where that spoken word comes from. There is a scholar named Walter Ong–who I looked at in my own studies for my Master’s Thesis–who looked at oral culture and degrees of orality.

Ong believed that there is something called “secondary orality”: in which spoken word is preserved through technological means like video and radio. But I’ve always wondered if he would have included illustrated images in this definition as well, and how problematic it would be if these images were accompanied by written words. Can the visual be considered part of the oral or the written, or is it something by itself? Obviously I’m talking about the medium of comics and what kind of literacy that would be defined as but–this tangent aside for now–right now I’m thinking about the idea of oral history being a historical narrative that records down what life and reality is like for “the common person”: if there is any such thing as a common person.

I actually think that this conception of oral history has led to the idea of journalism: of interviewing and recording down what a particular person or witness has to say, and then researching the environment in which this person came from for a greater perspective. Is journalism the child of oral history? And then you take something like Kenk into consideration too: something that is written down but also given a sequential FV Disco style is that is both an illustrative and video collage aesthetic.

It’s fascinating to think about Kenk as an artifact of not only “comics journalism”–a medium that some comics creators like Joe Sacco have already developed–but also written literacy, oral culture, history, and mass-produced art. I look at Kenk and I wonder if this is our contemporary version of the colportage of Menocchio’s time, or the pamphlets and photocopies of 1980s Slovenia. Because in the end, it’s not just Menocchio and Kenk that have a lot in common, but also the media used to try and capture what they are … and what they are not.

When I started writing this article, I thought it was going to be easy: like it was all fully formed in my head. In a way I’m doing what I said I would not do by delving more into the academics I’ve tried to put some distance from: at least with regards to jargon. My train of thought tends to drift and it has been a struggle to communicate and even cohesively perceive all of these parallels here.

But if this were a paper of mine, if this were some rough form of the Graduate essays I would write, I would end this post in the following manner. As someone who has studied mythic world-building, I believe that art is an engagement with different parts of the world around you, and an expression of who you are as a result of what you choose to accept of that world. In that, the man called Menocchio and Igor Kenk–specifically in how their scholars and artists portray them–not only made their own art, but actually lived their art, and allowed for the creation of more of it.

I also believe that when you take all of this into account oral history, journalism, comics journalism, or whatever you want to call it reveals one more truth. Writing about an individual not only reveals that there are no “ordinary people,” but that it never makes for making any “ordinary stories.” Ever.

Again, I’d like to thank Alex Jansen and Jason Gilmore for lending me these pages of Kenk to place here in my article to make both point and emphasis.

If you are interested in this topic, you might like my What is FV Disco article as well. They both deal with similar subject matter, but in different ways.