“He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorism 146

When last we left off in my article Life and Identity, Eden and Hell: The Twines of a Gaming Pixie, said Pixie left us in a second-person perspective hell of “You”: having left her penchant for placing us in the autobiographical of her Twine shoes and moving on to other worlds entirely.

But some things always come full-circle before revolving outward into a spiral.

Gaming Pixie writes a little bit about the origins behind why she made She Who Fights Monsters, this interactive combination of autobiography and fiction, far better than I ever could. If you want more information about that, read the previous link or look at her other posts on the subject on her developer’s Blog Gaming Pixie Games. This is not what I’m going to be focusing on.

Instead, I’m going to write about my impressions the basic plot and structure of the game, examine a bit of its creative evolution, and focus a bit on some of the game’s implications: especially with regards to its premise, its protagonist, and its ending. I will admit, right now, that I had a lot of trouble initially coming up with a way to write about She Who Fights Monsters. But it was Gaming Pixie herself who told me, when we last talked about the matter, to write about my own reactions to the game. There is something ironic about talking about the personal — about my feelings with regards to interacting with this game and its subject matter — in lieu of scrutinizing the autobiographical.

But in any case, do not read on if you don’t want to be exposed to potential triggers or spoilers. Reader’s discretion is advised.

It is no accident that this article begins with the above aphorism from Friedrich Nietzsche though, when the Alpha Demo for the game first came out, I had no idea this would even play a part in it. The Demo itself was called Fighting the Monster: which took place on Day One of the game’s chronology.

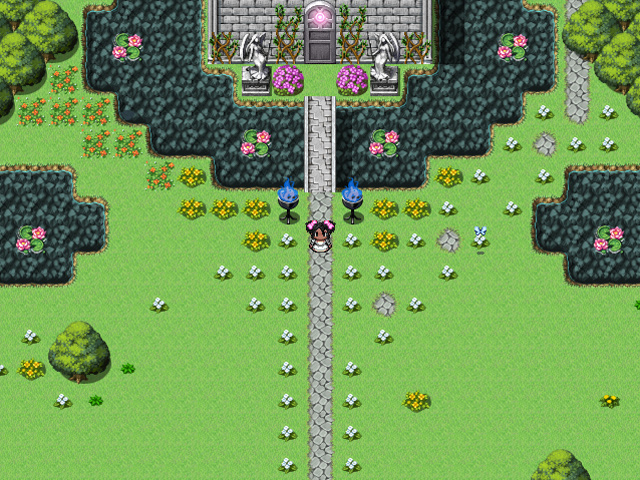

The story premise presented in this Demo translated over to the Beta Demo — called She Who Fights Monsters — and the subsequent game of the same name. You, the player, control the sprite of Jenny: an eight year girl who must survive the presence of a monster in her home for no less than seven days.

Of course, it becomes clear that Jenny’s battle is not merely with one monster.

This distinction is all the difference between two ideas embodied by the Alpha and Beta Demos. I will admit, right now, that I thought it would have been easier for Gaming Pixie to remain with, and work from, the spirit and aesthetics of Fighting the Monster. But make no mistake: both of them came from the same idea.

Let me try to articulate this as best I can. The overt antagonist, the monster, in She Who Fights Monsters is Jenny’s alcoholic father. Fighting the Monster, the Alpha Demo, was simpler. It was crude and more elemental for it. For me, it felt a lot more like a generic RPG: especially when you look at Jenny’s room and the imaginary haven inside her closet. But there was an old, faded texture to even these safe childhood places: like that of an old memory. The darker places, however, were dingier. Grittier. It set the tone of a stereotypical, old and dilapidated home where dysfunction and abuse are almost always typically depicted. And even here, it still felt like the aesthetic shell of an old 16-bit role-playing game.

And the monster is clearly Jenny’s father. If you judge the context by the Demo alone, he is the threat that Jenny must avoid. He breaks through all of her childhood illusions of magic, fairness, and innocence through cursing at her. Her Tears and her Innocence do not save her in the simulated turn-based RPG battle. In this one Demo alone, her father’s words feel like a slap in the face but the atmosphere of this world has been building to it. Even so, with Jenny’s mother’s revelation at the end of the Demo, that her father is an alcoholic, it sets a straightforward tone for the game and makes the Demo itself feel self-contained and continuous.

But Gaming Pixie never meant her game to be straightforward. So in the process of changing the game’s name, she also developed its aesthetics in the She Who Fights Monsters Beta Demo that would inform the rest of her game. And I will admit: it felt jarring at first.

Gone are the dinginess and grit and the fading of peeling memory on the walls. You find yourself with Jenny in a much more colourful and vibrant world. Her toys are brighter. The details around her stand out and the temple that is her imaginary place in her closet is grander and more elegant. Even her home looks more comforting: as much as any middle class home made by 16-bit pixels. Everything, even the nightmares, is vital and alive with colour: as much as any child’s world is at that age.

I feel it was designed this way: to make the player feel safe before immediately and brutally introducing them to the world of abuse and its effects on Jenny’s highly impressionable and figurative mind. And, this time around, when the trauma of encountering her verbally abusive father passes she finds herself in her room and her mother entering without even a single explanation. It was most likely made to function as an interactive preview in order create more ambiguity: so that the player could gradually, through the rest of the coming six days, see past the daydreams, imagination, and nightmares of a child to the adult reality of an alcoholic parent.

In some ways, it is even worse this way: to depict a normal childhood and have it impinged upon by the violence of an unknown and terrifying adult world, and the understanding that it will change Jenny’s life. It is a real life horror story of an ordinary world shattered by something aberrant and always lurking under a façade of normalcy.

I felt that both Demos were almost dress rehearsals for the psychodrama that was to come. The title itself says a lot: in that there is more than one kind of monster at work, and as such there are consequences for facing them.

So now we come to the real She Who Fights Monsters. The graphics are further improved — with even greater attention to detail — and you can explore Jenny’s entire house. Day One happens pretty much like it did in the Demos: with one interesting exception. Gaming Pixie ends off Day One from the part depicted in the Alpha Demo where Jenny’s mother flat-out tells her about her father’s alcoholism: the part that did not exist in the Beta Demo. And the scene where Jenny goes out to get some cookies becomes a background reminiscent of strange organic Giger-aesthetics of the horror game Yume Nikki or the Earthbound Giygas battle.

You, as the player, now know what you are facing and you must play through the remaining days. Yet there is one more thing that you need to consider.

The Memory Bloom is a giant flower that you find past the Temple in the closet. It didn’t exist in the Alpha Demo and I almost missed it in the Beta until Gaming Pixie pointed it out in one of her developer’s blog posts. In the Demo the Bloom itself tells you that it will only become important in the main game and, make no mistake, it is crucial. You will get Locked Memories throughout the game and it is critical to interact — or not interact — with this flower. If you do, you will also realize that not all of Jenny’s memories and experiences with her father are bad. In a lot of ways, it makes it even worse: in that these positive moments and traits in an abuser often make a victim feel bad in attributing negative emotions to that person. It makes the situation all the more complicated than simply Fighting the Monster. What you decide to do will determine Jenny’s future.

After all, it took Seven Days, in the Christian New Testament, for God to create the world and its inhabitants and She Who Fights Monsters demonstrates that seven days can create an entire human being depending on the choices that you make, and how Jenny responds to the monster in front of her and the ones forming inside of her head.

There is a quote often attributed to the writer G.K. Chesterton which states that “Fairy tales are more than true — not because they tell us dragons exist, but because they tell us dragons can be beaten.” However, there is another quote, from the fantasy and horror writer Stephen King that is also equally true, that “Monsters are real, and ghosts are real too. They live inside us, and sometimes, they win.”

These are both words to bear in mind as you progress: when on the Seventh Day even the illusion of childhood safety will be ripped away and Jenny will have to start on the path to self-actualization — to adulthood — far sooner than she should. For me, that and my scary and heartbreaking decision to unlock her Final Memory were the hardest parts of this game: to deal with them and to determine what Jenny should do beyond it.

Do you remember when I said that in some ways She Who Fights Monsters is a subversion of a 16-bit RPG? This still holds true even past the Alpha Demo: but in an even more subtle way. I mean, you already understand from Day One that any attempt to fight the game like it is a turn-based battle will end in failure. You already know that not fighting will end in failure. The fact that the game narrative text boxes are in third person-limited perspective, always referring to “Jenny,” “her,” and not “you”: the distance only provides you some illusion of safety.

The perspective is perhaps designed to make you feel that disassociation that a child facing ongoing emotional trauma and abuse would experience: only made more jarring during Jenny’s first-person interludes. These narrative perspectives are very notable departures from Gaming Pixie’s previous Twine-based games: not unlike Christine Love’s don’t take it personally, babe, it just ain’t your story where you are not the character, or even acknowledged as a player. This simply isn’t your story, even if you do influence it.

And when the game does get to the point where it feels like a turn-based RPG battle? Be careful — be very careful — because the thing you need to remember is the end of the first “battle” with Jenny’s father, particularly the words, “Nobody wins.”

The subversion goes deeper when you also consider that there will come a Day where Jenny is hiding in her room and there are clues around. They are extremely clever elements of potential foreshadowing and they are a nice contrast to the beginning of the first Day. For me, the freedom of exploration in Day One — of finding the bathroom, the kitchen, living room, basement, and crawl space — seemed to set up the beginning of a horror survival game, of knowing all the hiding spots and thinking you have discovered potential secrets only to make it purely about the psychological and the inner world of demons. Aside from the clear mindscape influence of the Silent Hill series, this game is reminiscent of the game Eversion in that sense: only instead of the aesthetics and gameplay changing over time from something brighter into something grimmer, it is a dynamic that goes back and forth between states of atmosphere — always in Jenny’s head, because we are all seeing this from Jenny’s head — until a final decision is made.

When I first heard about the concept behind what would become She Who Fights Monsters, I was reminded of another game based on a child creating an imaginary world to deal with an alcoholic parent called Papo & Yo. Yet aside from the fact that both games have autobiographical elements, child protagonists, and monsters for fathers that hurt them even as they love them there are obvious differences. Papo & Yo takes place in a fantastic equivalent of a favela –a Brazilian slum — and in all realities it is three-dimensional, while despite the aesthetics of its Alpha Demo She Who Fights Monsters takes place in a normal looking middle-class home. Monster, the Papo & Yo protagonist’s enemy is sometimes his companion when he isn’t in a rage, while it is clear that despite some good memories Jenny’s father is never really her friend nor does he help her in her game. While Papo & Yo is more distinctly a puzzle and deadly hide-and-seek game, She Who Fights Monsters is indeed a story that you mostly observe: sometimes very helplessly. And, of course Quico is a young boy and Jenny is a young girl.

You might think that the latter distinctions mean very little and indeed, they are both children placed into situations that no child should ever have to deal with: confronting their parents as enemies. But then there is the elephant in the room to consider. In a segment of her article regarding Gaming Pixie’s epic Twine game Eden, Soha Kareem observes that the former is “an accidentally political game.”

The fact is, Jenny is not only female but she is also “a person of colour.” It can’t be stated enough that, at least to my knowledge, just how rare and unique it is to be playing a game with a young Black girl as its protagonist: in her own story. In a medium that is still struggling to represent different identities in its games, it is definitely something to take note of. However, I am not qualified to talk about “race” or its implications: and how the race and class of Jenny’s family affects her story, if at all, is a matter I will leave to more capable writers than myself. Indeed, this matter seems more “incidental” than “accidental” and Gaming Pixie herself is more focused on the situation and survival of Jenny as opposed to her background.

But there is something else I’d like to note that Soha Kareem also states. In her writing on Gaming Pixie’s Eden, she points out that “The game’s endings and achievements are determined by your karmic choices.” She goes on to explain how, in Eden, how Gaming Pixie subverts the video game trope of the protagonist needing to manipulate their love interest as an object into a relationship by making it so that the player must genuinely act like “a good person” in order to gain that level of trust. The point is, Gaming Pixie is both sneaky and honest in the sense that your choices have clear moral consequences. Even in She Who Fights Monsters, depending on what you do with the Memory Bloom and what you choose to remember, some paths will be open to you, some closed, and some will exist only for one tenuous moment of conscience.

I won’t spoil the endings for you, but I will say this. When I play a game, particularly one with this kind of detail, I like to get all of its information so that I can actually make an informed decision. Even so, remember what I mentioned about being careful when you find yourself in a combat situation in this game? Well, if you make a certain choice and you like to be violent and go all Sith you should know that, if you do, there are consequences. You may become the monsters that you are fighting, the demons in your mind, and it might well lead … to a whole other game entirely.

So please, download Gaming Pixie’s She Who Fights Monsters — which is supported by donationware — and determine how this horror story ends, and where others might well begin.