“I like games with consequences.”

This is what a friend of mine told me not too long ago with regards to online games, but it is a sentiment that can easily be applied to video games in general. I know that I–and many other more eloquent and informed people on the matter–have stated that the medium of the video game can be used for more than just entertainment value. The medium of a video game is as its very core an interactive experience that, like any other art form, can get us to relate to the world around us in a different way.

However, with regards to Pipe Trouble, there is also the matter of responsibility to consider as well.

Pipe Trouble is a game created by Pop Sandbox Productions, produced by Alex Jansen, and co-designed by Jim Munroe. It was apparently made as a companion piece to the TVO-commissioned documentary Trouble in the Peace: a film directed by Julian T. Pinder and produced by Six Island Productions about gas leaks affecting Northern British Columbia farmers in the Peace River region and in particular one man and father, who has decided to do something about it.

Before I decided to write this article, I did not know that Pipe Trouble was a digital complement to this documentary. In fact, the entire subject matter that both the film and the game seem to encompass–Canadian farms encountering potentially lethal gas leaks from pipelines of gas companies in their regions–is not usually something I tend to focus on with more than passing attention. After a while, and as cynical as it gets, news of “corrupt corporations, victims and innocent bystanders, and eco-terrorist reprisals” tends to become oversimplified by the media.

It is one thing, however, to hear and watch something about a matter that seemingly doesn’t concern you as an individual. It is a whole other thing to find yourself in a situation–even if it is a simulation with a satirical veneer–where you are in a position of great responsibility.

What Pop Sandbox is attempting to do to this regard is not something new, but rather it is a very familiar idea they have worked with expressed into a different medium. While I did write an article or two on Kenk: A Graphic Portrait a fair while ago, what I might have neglected to mention is that one major theme in the graphic novel–also made by Pop Sandbox–is that everyone has a part to play in a particular social action. In the case of Igor Kenk and his stolen bicycles, it is made clear that everyone–to the people who bought bicycles from him, to even the people who purchased their stolen bikes back, to law enforcement and Toronto City Hall–knew about what he was doing and, just as they condemned it, they also tolerated and even to some extent accepted it a part of their social system. With regards to Kenk, Pop Sandbox illustrated–quite literally–how Igor Kenk was just part of a social dynamic–of a collaboration–in which the rest of the city was also a part.

But Pop Sandbox goes even further with Pipe Trouble. While Kenk simply observes a social structure and interaction, Pipe Trouble makes the player-audience interact immediately and directly with the issue as clearly, and as simply put, as possible.

In other words, you–the player–are placed as the manager of a gas company apparently situated in the Canadian Province of Alberta and you must please your superiors and make them money, keep the people who need your corporation’s services in mind, do as little damage to farmland, animals, humans, and the environment as possible, and try not to piss anyone off.

It is very clever. It is very easy to vilify a company or a corporation as a soulless entity that only caters to the very rich, squashes agriculture and “the lower classes,” and pollutes the environment without any understanding of what it might be doing or–worse–even care. It is just as easy to lionize a pipe bomber as a freedom fighter against a tyrannical force even as it is to denigrate them as a terrorist that likes to destroy human lives and a Western way of life: whatever that is.

However, natural gas is one of those resources necessary for a modern society to function and a corporation is made by people. As such, someone has to be in charge of providing that corporation’s service, making a living from it, avoiding bad press and blame while attempting to integrate their industrial system into the environment and those existing within it with as little damage as possible. It is no tall order and not an enviable position: especially when you are forced to do it in a game.

It is no coincidence that this game is modelled after the 1989 puzzle game alternatively called Pipe Mania or Pipe Dream. And even though the title itself brings to mind some bad bodily jokes, even that connotation has its point when looking at the game. In Pipe Dream, you have to build pipes to direct the flow of filth inside of a sewer. Pipe Trouble takes a similar mechanic and makes the oncoming substance also toxic, but also worth money. One person’s poison is another one’s livelihood.

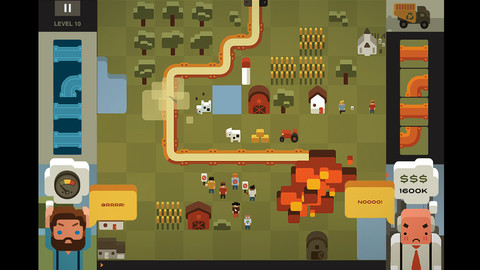

You have two men on either of your screen. I would be tempted to call them “the angel” and “the devil” on either of your shoulders, save that both of them aren’t necessarily “good” or “evil.” The man on your left is a farmer that is watching your progress in placing down pipes with oncoming gas with great interest and caution. If you destroy the land too much, there will be protesters that will block your pipe route. How long they stay in front of your progress will all depend on just how much damage they perceived you to have done. This farmer will keep watching you and will warn you only once not to mess with his land.

Then you have the man on your right: your boss. He is the one informing you of when the gas will start flowing (right when you place a pipe down to get from Point A to Point B) and he will keep track of the money you are making … and losing with delays. That’s right. If you do not place your pipes fast enough, not only will you risk a gas leak poisoning a lake, killing animals, and other horrors but you will lose your company money and your boss will sure as hell hold you responsible and, if we are going for realism, probably put it all on your head when the bad press comes out.

I swear: when I first played this game and that gas started to flow and sometimes I didn’t move fast enough, or have the right pipe piece to place down or even put it in the proper place, that sense of panic sets in. Then you add the pixilated animals that prance and eat in the woods and you are thinking real hard about how to not disturb them: never mind potentially kill them. And that is not even including the fear of getting more protesters in your way that will get more organized and then sometimes even use some nice industrial sabotage against your pipeline: causing more death, destruction, money loss, and bad press. And guess who would probably be held responsible for all of that?

You’re looking at yourself.

It’s like playing Tetris … only with people’s lives. And remember how I didn’t make any bodily function jokes? Well, the ideal is to treat the entire process like the human body. The release of energy, the disposal of waste, and the structure of what you are trying to build is supposed to create a balance with the ecosystem, agriculture, and animal and human health. But as you play and it gets harder, you will become aware of the fact that this game is an idealist’s nightmare. You will have to make some very difficult decisions as you realize that you might not have time to build around that forest to your pipeline’s destination or you might have to be innovative and make some alternate routes in a very set time frame, but in the end you will have to make some very hard choices.

Do not let the game’s cheerful 8-bit pixilated graphics and basic soft-edged square shaped sprite characters fool you. Jim Munroe was also co-designer behind this game. He is an independent Canadian science fiction and comics writer, among other things, that likes to take grandiose topics like haunted TTC Stations, North America becoming destitute in a futuristic era, and a post-apocalyptic world after the Christian Rapture and completely twist them upside down and make it about human characters and life going on. More than coincidentally, Munroe is also the Hand Eye Society’s Project Coordinator for the development of the Torontrons: essentially retrofitted arcade cabinets that play newly made video games. He may have been involved with the pretty nifty creation of the Pipe Trouble game cabinet as well: which, as the link explains, will be placed in areas of high traffic such as universities, city centres, and tourist attractions.

I don’t know what else to add here. Inter-dispersed between levels are radio segments from news anchored events dealing with natural gas industry controversies which I didn’t originally hear until I played the game again at home on the free trial demo. Also, not too long ago I found out that the game itself has created a whole lot of controversy. Apparently TVO–one of the game’s sponsors–has been accused, among other things, of potentially giving eco-terrorists “ideas” by supporting the creation of the game. TVO has apparently removed links to Pipe Trouble from their website with pending investigations into the matter on their end to see if they were in “the wrong.” There seem to be some definite misunderstandings over various issues, but if one goal of this game is to encourage people to think, then controversy–though unfortunate–is one way of getting there. Either way, it definitely hit a nerve in that intersection where art and politics clash.

I think my concluding thought about this entire game is that the title “Pipe Trouble,” again, can mean a lot of things. And it wasn’t until I read the above article that I began to think about it a little more. I don’t generally look at these kinds of games, never mind write about them–especially with how close it comes to politics–but there is something really fascinating about the dynamics that Pop Sandbox attempts to create, identify, satirize, educate and help people relate to. And politics itself is an exchange of power and watching how and through what medium that power is ultimately exchanged through.

You see, I’m looking at pipes as symbolic of devices that link us together and support a communication of ideas. They can create a very interactive and comprehensive system of healthy self-regulation but when there are so many elements in play, things can go wrong, words can break down, and people and the world around them can suffer for it. But whatever else this game accomplishes, it definitely makes you think about these issues and how they are not entirely separate after all: neither from each other, nor from you.