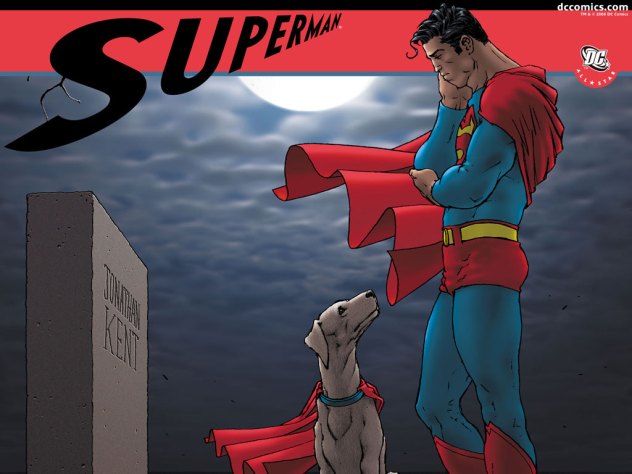

The super-hero genre is something that has not only cross-pollinated into different media, but has–in itself–been subject to a considerable amount of scrutiny. Superheroes have been changed into gritty, horrifyingly realistic beings by the Revisionism…

The super-hero genre is something that has not only cross-pollinated into different media, but has–in itself–been subject to a considerable amount of scrutiny. Superheroes have been changed into gritty, horrifyingly realistic beings by the Revisionism…

Category: Sequart Articles

Working On A Comics Script and Submissions

I thought I should make a proper update while I still have some time.

My Displacement Twine became something of a one-off project that I came up with late at night while I’ve been dealing with other matters. I’ve already mentioned that I’ve got ODSP and I didn’t, in fact, have to go into a hearing as my community lawyer settled it “out of court.” It takes a major load off that’s been weighing on me for the better part of a year, but even though I know there will be more challenges and annoyances ahead, it still feels like progress.

But now for the stuff that you don’t know about.

A little while ago, I was a student at Ty Templeton’s Comic Book Bootcamp Writing for Comics course. During that time, after doing many assignments, we were supposed to hand in a script: in order to get feedback from Ty himself. Unfortunately, due to life’s circumstances I was only able to submit a rough outline of the script that I wanted to write. So I found peace with that in order to get at least some feedback from Ty.

Instead, he gave me a considerable amount of feedback and actually wants to see a completed script.

So that is basically why I’d been gone for a month. I’ve been working on my comics script to show Ty Templeton. So far, I’ve finished the Story Mapping phase: where I try to approximate the story beats and pacing on each page. It’s actually made me look at details I might have missed before and even given me the opportunity to hone down other aspects of my outline. I had so much more to say about this a little while ago, but I have been busy. Suffice to say, though, I’m drawing it out by hand in my Mythic Bios notebook with my 1989 Batman movie pencil that you can, no doubt, see in the graphic of this Blog post.

It’s sad because I know there are other insights I could talk about and refer back to, but basically for me this has been creating the skeleton of my story which, considering its subject matter, is very appropriate. But basically I am outlining each page, sectioning it off into threes, and placing the basic idea of what happens in every section followed by beats to show what happens in each panel of that section on each page.

But now I have entered the Storyboarding (wow doesn’t that sound like some kind of psychological torture technique) Phase: where I am going to have to approximate what visually goes on in those panels. Much of this is going to start off with me reviewing the notes I’ve taken from Ty’s class to the point where I’m confident in drawing it all out with crude and inclusive stick figures that I will have to describe with thorough wording for the Writing Phase of the Script: and that doesn’t even include the dialogue and captions that I need to write clearly and distinctively.

Then I’m going to show it to one of my fellow classmates, Kim — who is awesome — and then submit it to Ty when everything is said and done. But yes. I even have plans for further stories after this one, but the World-Building Phase — which includes more descriptive writing — will have to continue along with my capacity to do so and remember that an artist needs to know details but also have the freedom to do their own thing.

I’m almost done with my update. But script writing and submission aside, and have the attention span to finally sit down and knock this post out, I also want to mention that I’ve applied for a writing position in an online magazine called Panels: a place that talks about comics, comics subcultures, and the writer’s reactions and insights into them. It’s right up my alley and it’s a paying job.

Some of the sample works I’ve sent them include: When I Recognized Elfquest and Chasing Amy and Reviewing the Laurel Leaves. So we will see whether or not I get accepted into their ranks and, if so, it is definitely an exciting start.

So yes. A lot of stuff is happening on my end, finally, and I just need to keep at it while — at the same time — I also need to pace myself. I don’t know when I will write here next, but hopefully I will have more to talk about and more to report.

Take care everyone and thank you for continuing to follow me on this journey.

Displacement: A Twine About A Learning Disabled Experience

People almost always gravitate towards personal stories. I’ve probably said this already in some way or form, and I know if I haven’t many other people have.

For the longest time, even though I’ve been very busy, I’ve wanted to have an excuse to make another Twine story. I almost did a few times: such as when I was tempted to create a Twine called Bureaucracy Quest in which you have to go on a scavenger hunt of varying documents, while keeping labyrinthine and mandatory appointments, while running into dead-ends and recursive story loops which are specifically designed to make you shut off the Twine from complete and utter frustration. But, fittingly enough, I didn’t have the patience to make this game while living the experiences that inspired it.

It was one night, between other projects I’ve been attempting to work on, that the cynical idea came to me. I was still waiting to hear back from my legal counsel as to whether or not I was going to get on the Ontario Disability Support Program settled out of court, or if I were going to need to attend the hearing that was going to happen this month. The good news is that the community lawyer working on my case was excellent and got me onto this new system. But at the time, I’d been waiting to hear back from ODSP for about a year and I didn’t know what was happening at the time.

There was a series of muscles I must have been holding for over a year, and a few days before I finally heard the decision on the phone from my lawyer, a lot of different elements began to gather in my mind. It began with the first rejection letter I’d ever gotten from ODSP: essentially stating that according to their guidelines I didn’t have a permanent disability.

I had been diagnosed as being learning disabled, as being what nowadays might be called “non-neurotypical” since I was a child. I had to attend special kindergarten, then classes, and then alternate classes. I had an especially hard time in high school: as I only had one class that dealt with learning disabilities and I had to get extra help from the teachers themselves without much in the way of a department to back me up.

My plan was simple. I had gradually weened myself off and away from the programs that I had difficulty completing. I mean, you can imagine how disabilities such as dyscalculia, spatial difficulties, and even challenges in hand-eye coordination and mental focus — in needing finer instructions — can get in the way of mathematics, geometry, fine arts, geography, and even aspects of the hard sciences. Phys. Ed was especially bad for me due to physical coordination issues. So I got through them with the bare minimum. And then I replaced them with philosophy, sociological, historical, and literary courses. I focused on what I was strong in doing: and even then I needed special help with regards to tests and exams.

But I was told, and I hoped, that by University I could take the courses that I wanted and build the education that suited me: making me ready for a career in academics. I was going to focus on my strengths and leave my weaknesses behind. I was going to make it so that my learning disability was irrelevant and I wouldn’t have to identify with it anymore. I believed that I could succeed through sheer merit, through personal work, discipline, and sacrifice: and that, with some help and support behind me, I could excel.

What I didn’t understand, at the time, was that our society is not — and has never been — a meritocracy. It is a bureaucracy: with specific rules and procedures. Networking is also a social skill that is integral to navigating the labyrinth. And while I had instructors and academic representatives that told me about the importance of this element, I just couldn’t relate to it. Not really. Again, I thought it was about what you did and not who you know: or even who knew you.

Then there are the psychological factors to consider. Other kids are hyper-aware of differences and if you have trouble socializing, or counting fast enough, or telling directions, or the fact that you rock back and forth when you are excited or nervous and your hands fidget, or even when you talk to yourself they will notice. They will notice and they will laugh at you, or bully you, or avoid you.

And those are just the children: your peers. I’m not even talking about the adults. Between having my grandfather thinking of my math disability as a sign of laziness, and others snapping at me to stop fidgeting or talking to myself — for fear that I would “look ridiculous” — you can already understand why I’d want to leave that all behind me. You can also more than imagine where a lot of my anger comes from, and where some of my own present difficulties spring.

I was also lucky. My parents recognized that I had cognitive difficulties and got me as much treatment for them as possible. But as such, most of the family emphasis was less on me learning life skills as it was actually succeeding in school: as that was a major difficulty of mine. But it cost me: as by the time I moved out a few years ago, I didn’t really know how to take care of myself. I didn’t really have a stable network of people to help me with that, and I was left to figure out a lot of these things on my own, or deal with people and organizations that gave me basic — or bad — advice and nothing really of substance.

There was a lot of weight on my mind in getting through my Master’s and juggling real life: and I hated, absolutely resented the idea that my learning disabilities — that the make-up of my brain — was still affecting me despite all the calculators and GPSes of the world.

So you can imagine that when I finally swallowed my pride, the first time with Ontario Works, and the second with ODSP that when I got my first rejection letter telling me: “By our guidelines you do not have a permanent disability” that it was the equivalent of a slap to the face.

I had a long time to think about this. It took a while but I had to accept that my disabilities, that my “non-neurotypical” brain are still parts of my life. It took me even longer to embrace the fact that I have to identify what is just another wiring of my brain and experience as a disability: in order to get the current social structure to help me survive it. I thought about all the people that have told me to “suck it up” or just tolerate what I can’t focus on in order to exist. I’ve had to fight against the idea that I am “coping out” when I identify as being learning disabled instead of “earning my place like everyone else”: whatever that means.

And so I decided to call ODSP on its punitive structure. I sent in my forms and my diagnosis from my therapist, which they rejected the first time. I had them do an internal review, in which they found no fault in their decision. And then I faced down a hearing in a game of “Chicken” to see who would give way first. I am a really stubborn person when I have a mind to be. In fact, I do extremely well when I have something passionate and real to focus on instead of settling for something less than.

I’m also aware of how privileged I am. Between my family that actually recognizes learning disabilities and finds itself there for me, to the community counsel that got my case settled out of court, to the best therapist I’ve ever had with or without Canadian OHIP, and a lot of Affirmative Action protocols, I have been exceedingly lucky. And I know that just as all learning disabled people aren’t the same, many others haven’t had — and don’t have — the backgrounds or resources that I do.

But there is one other thing that stuck with me after that experience of having my disability and experiences not acknowledged until I faced them head on. I thought about how we all experience and interact with the world. And that night, a few nights ago, when I was thinking about how best to communicate what it was like to be in the world with a learning disability, I came up with this idea for an interactive story.

I asked myself this: how would someone navigate a world if they had trouble reading maps or telling directions? What would it look like, in words, to see someone with dyscalculia doing equations or basic math? How would I portray the psychological baggage that comes with dealing with these issues since childhood? Can I do all of this and show they have something of a commonality?

And can I communicate my experience — my voice on this — through a creative medium with which I still have limitations? Can I express my story simply through the description of perception and emotion?

I realized, a few days before the bittersweet moment of finally having ODSP recognize that I have a permanent disability, that living with spatial, mathematical, and even body movement issues is like existing out of the same space-time as most people. You are somewhat out of synchronicity with the rest: both cognitively and socially. And that was where I eventually got the name for my story idea the following day.

It’s by no means an exhaustive story about all learning disabilities, or even the different gradations of the ones that I possess. It came out very rough in its first iteration — I had to par down the psychological elements — and even now I think I could have portrayed the experiences of the narrator more effectively: such as using that recursive loop of repeating hyperlinks I mentioned earlier to symbolize getting physically lost. But I also don’t know how accurate that would be and, honestly, I think right now this is as good as it gets.

This will have been my third post dealing with learning disabilities on this Blog: or at least the latest one after my experiences from this past summer. I hope, after this, to go back to writing posts about video games, comics, fictional universes, and projects that I’m working on. Those are the things which I want to be known by and remembered.

That being said, I would like to thank Gaming Pixie for looking over and providing input into the Twine story that I have linked above. Whatever else, I hope you find the story, and this post, educational at the very least.

Time Travel and Retconning: Revisionism and Reconstructionism in Doctor Who

Just as the New Year is approaching, so is “The Time of the Doctor.”

I’ve come out of hiatus again, essentially, because this is another thought that just won’t leave me alone. After I was exposed to Julian Darius of Sequart’s distinctions between Revisionism and Reconstructionism with regards to comics, I applied it to my article In a Different Place, a Different Time: Revision and Reconstruction in Comics Without Superheroes? Of course, I should have realized it was not going to end there.

I mean, come on: I already mentioned space and time in the aforementioned article’s title. And after a while of gestation and trying to stave it off, I knew what was going to happen. I was going to provide the distinctions of Revisionism and Reconstructionism, taken from Julian Darius, the latter term apparently coined from Kurt Busiek, to the development of the Doctor Who series. Let’s face it: this was just going to happen and, if we’re going to be honest with each other, it probably has in no so many words and in ways that have been covered far more exhaustively than I am going to be.

So let’s get to the point and quote River Song, as I tend to with a lot of the Doctor Who articles I’ve written, to say, “Spoilers.”

This is really going to be a brief case of looking at parallels between the development of the superhero comics genre and Doctor Who. Like the early comics versions of Batman, Superman and others, The Doctor as a character starts off as a relatively morally ambiguous character: someone who isn’t necessarily evil, but not always good. Certainly, they all have the power to impose their will on others whom they don’t agree with, or are quite willing to let someone destroy themselves as opposed to interceding on their behalf. The Doctor himself, in his very first incarnation was more than willing to abandon people to their deaths if they became “inconvenient” to his or his granddaughter’s own survival.

And this was in the 1960s. Superhero comics themselves, especially the ones I mentioned, existed from the 30s onward: from that Golden Age period where superheroes were still trying to get past their “might is right” mentality to reveal at least some of the heroism that we recognize. The Doctor, however, had an even more interesting challenge: in that he was a character in a science-fiction program that drew on a tradition of science-fiction programs and stories. He wasn’t exactly a hero then and never quite fit that mould well. He and his Companions were more explorers and, as such, the program was one of exploration that bordered on a weird sort of horror: the kind of horror that, well, basically came from the spectacle of science-fiction B movies, comics, and pulp stories before it. Even the early Doctor Who episodes, from I’m given to understand, have a very pulp and serial feel to them: with constantly interrelated chains if episodes making a story followed by standalone episodes and “monsters of the week.”

Of course, things changed for both superhero comics and Whoniverse respectively. It was the Comics Code Authority that greatly white-washed many of the darker elements away from superhero adventures. Some of them simply didn’t survive and became silly caricatures of their original selves. This wasn’t always the case and some stories managed to be told well even in the midst of not being able to question authority-figures among other things. Towards the sixties, however, there were many campy and downright silly elements amongst this genre of comics: particularly with regards to Batman and such.

Doctor Who, which started in the sixties, always had an element of the uncanny and the weird in itself. It also had elements of camp and strange, tangential adventures. For some time, the BBC had a low budget so they basically had to utilize B movie props and effects to make their monsters and their stories. And The Doctor himself became a lot more of a swashbuckling character or archetype: embodying different ideals but becoming somehow more human as time went on. The humanization of The Doctor, which began with his Companions from his early days, contributed to this and probably in no small part due to the fact that the program began as a children’s show.

But just as there were so many disparate elements and strangeness in the Silver Age of superhero comics, this was definitely the case with the original Doctor Who series. What is interesting to consider with regards to Doctor Who however is that many “silly costumes and props and styles” have become iconic in themselves and even popular in a vintage, classic, nostalgic sort of way among fans. The books and audio dramas also helped to expand many of these elements and add more to the quantum branch of reality that was the Whoniverse.

It was in the 1980s that things began to change for superhero comics. This was when Revisionism came into play. Writers like Alan Moore and Frank Miller asked themselves the question of what a superhero would be like, with the powers and abilities they possessed, in a realistic situation. They were also mindful of the pessimism, cynicism, and fear around in this particular time period and wondered how the hero would function in such a world: and what they would do to that world. This is the period in which the superhero really got dissected. Writers in this time and onward seemed to draw on the ancient classical designations of “hero”: of a person of spectacular power and skill that bordered on, or were totally amoral, to reshape the heroes of the 30s and 60s. This allowed much in the way of character development and the creation of truly epic story-lines. Of course, the danger was also created: that the dark grittiness of Revisionism would become a form onto itself and not a vessel to tell a carefully thought out story. Darkness for darkness’ sake, as it were.

With Doctor Who, I argue that its Revisionism came in 2005 with the beginning of the new series. After a gap from 1989, and television movie in 1996, The Doctor returned in 2005 under a very different premise from his earlier adventures. It is almost like producer and screenwriter Russell T. Davies created his own Crisis on Infinite Earths and destroyed much of the quantum and tangential branches of the old Whoniverse in order to create a very centralized, dark, and Byronic reality: as though he and others believed that the only way the program could survive would be to “mature” into this new spirit. It is as though they expected viewers to want something less silly and more “realistic.”

So there was a Time War, the Last Great Time War, that seemed to have obliterated many loose-ends (and cause no small heap of trouble in the loose-ends that did, in fact, continue to exist for the Universe) and leave a Doctor that was more gaunt, more lonely, and far angrier than many of his other incarnations before him. The children’s show origins of program seemed to have been burned away by rage, an attempt at a more serious tone, singular purpose, and Revisionism.

Even the inclusion of David Tennant as the next Doctor, who was a marked contrast to the sullen leather jacket-wearing Doctor who somehow began to lighten up a bit towards the end, only accentuated this kind of Miltonian grandiosity. He might as well, in a ridiculously sublime way, have been an angel from Milton’s Paradise Lost sailing through a perfect clockwork Universe skewed by Original Sin, or perhaps as a far livelier Virgil figure in a kind of Dante’s Inferno of wonders. When Steven Moffat took over as producer and the Matt Smith incarnation of The Doctor came in, the youngest depiction there has ever been (he is about my age), the dark elements were beginning to wear a little thin.

But there is something truly wonderful that was forming with Doctor Who, and its spin-offs Torchwood and The Sarah Jane Smith Adventures. Despite the darkness and the angst of The Doctor being “the last Time Lord,” there has been a great depiction of wonders. I’m not just talking about the more advanced CGI or sophisticated props and costuming provided to the program. I’m also talking about its embrace of diversity: about its inclusion of different cultures, race and even sexual orientations. And it doesn’t seem to display them as novelties but as givens. As science-fiction that, by its very nature, encompasses the future and its possible sensibilities in addition to all of space and time it is extremely encouraging to see. It might have something to do with the fact that Russell T. Davies is gay himself and wanted to include diversity, but there is also the fact that Doctor Who is the longest running science-fiction show in existence and it changes with the times and the attitudes in each era in which it finds itself.

But the sense of wonder that is, in the words of the program’s first producer Verity Lambert, “C.S. Lewis meets H.G. Wells meets Father Christmas,” is so much older than this and it wins out over the darkness every time. It is similar to the sense of nobility and kindness from Superman or the sure sense of justice from Batman. You can also call that sense of wonder hope.

By the time of Steve Moffat, whose episodes are strong in a self-contained short story fashion but whose overall structure begins to unravel the strong Miltonian clockwork of Davies with plot holes, much in the way that the Cracks in Time began to appear, or how the Weeping Angels feed off of temporal rifts and die from paradox-poisoning (which is ironic when you consider how Moffat created them in the first place and that his stories have many plot-holes), you may be witnessing a change beginning to happen. From 2005 and onward, most of Doctor Who has taken place on Earth or has focused almost solely on humans and has maintained a relatively linear story line and premise.

But then Moffat did something. By 1995, Julian Darius argues that Revisionism in comics began to change. Writers such as Grant Morrison began to look back on superhero comics before Revisionism and draw on the idealism and hope of those periods. They took the character-writing and plot development of Revisionism and combined it with the light-heartedness of heroes against the darkness. They, arguably, contributed to the creation of Reconstructionism.

And Morrison himself was known to have really liked the strange and wacky DC elements that existed before what he considered to be a cynical Crisis plot: perhaps much in the way that some of The Doctor’s fans might view his present “gritty and realistic” situation.

Now look back at Steve Moffat. In “The Day of the Doctor” he took the premise of The Doctor having destroyed the Time Lords and, in a typical time-travelling fashion, changed and retconned time. He had The Doctor and his previous incarnations save Gallifrey. Now The Doctor has to go and find it. In one stroke, however it was executed, Moffat eliminated the heart of The Doctor’s modern angst. And in the next episode, in the Christmas Special “The Time of the Doctor” we are going to see him fall to his lowest as he is apparently on his “last incarnation” and is going to die. But we know that isn’t going to happen. We know he will survive. We know there will be a new Doctor.

And perhaps, just perhaps, this is Moffat’s attempt to apply Reconstructionism to Doctor Who. Certainly the inclusion of Tom Baker, the former Fourth Doctor that represented The Doctor’s kindliness, affability and wisdom, into “The Day of the Doctor”–representing what could be another future incarnation of the Time Lord–can be interpreted as a sign of that return to some the weird, and wacky adventures that possess no small amount of hope.

But whatever the case, we are going to see Peter Capaldi as an older, but perhaps wilder Doctor: someone who is not a soldier, a traumatized war veteran, a hero with an anguished dream, or a lonely boy but an adventurer and traveler. He is going to look for where he put Gallifrey. He is going to go out again. Perhaps he might even leave Earth in all time lines and we can see how the rest of the Universe has been doing, how other worlds and newer beings live, and how he will interact with them. Maybe after all the time that Davies has reforged the content of the program it will open up back into larger vistas beyond just Earth and the human.

There is just one last Battle of Trenzalore, a Regeneration rule to work around, and then perhaps the potential for some reconstruction, for something new, for something old, and for something new again. Either way, I look forward to the journey.